One of my favourite things that I spotted in the second half of the third season of Bridgerton was the presence of cabinets of curiosity in Penelope and Colin’s sitting room. It seems the perfect set addition for our intrepid and intellectually engaged couple (I tried to find a still of the set, but couldn’t!): why wouldn’t they have their own mini museums of objects on display? As someone who has spent a lot of time researching collecting and cabinets of curiosity, I am not ashamed to admit I squealed and paused the episode when I saw this design detail.

But what actually is a cabinet of curiosity?

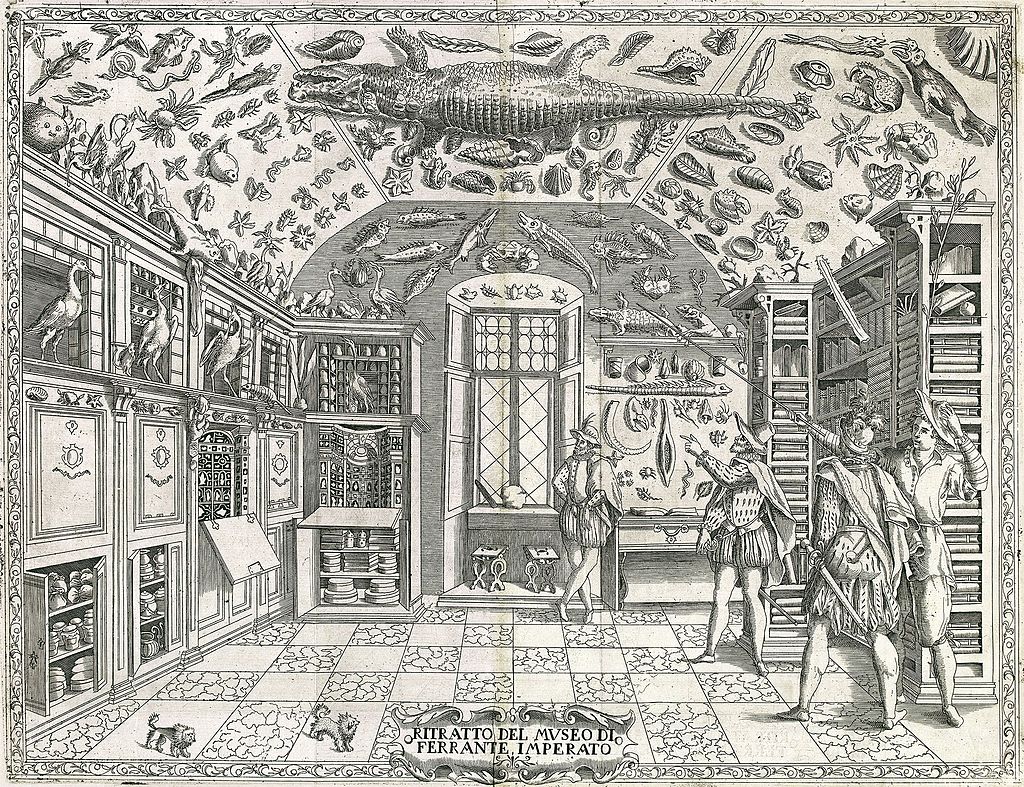

They were literal physical spaces to hold objects and specimens, including drawers, shelves, boxes, open areas and ones hidden away. They were a precursor to museums, that collectors would sometimes open to their friends, acquaintances, networks and the public to engage with the objects within.

Preceded by vaults, treasuries and reliquaries, we see the first use of the word “Wunderkammer”, German for literally a room of wonder, in the second half of the sixteenth century, as well as the publication of the first work on building cabinets of curiosity and advising on the act of collecting.

This was written by the Belgian-born, Germany-residing Samuel Quiccheberg, and published in 1565. It was a treatise that played a pioneering role in the development of the culture of curiosities and collecting across Europe, entitled: Inscriptiones vel Tituli Theatri Amplissimi. Quiccheberg’s definition of what a collection should be is as follows:

“A theatre of the broadest scope, containing authentic materials and precise reproductions of the whole of the universe”.

The book is actually surprisingly mundane, in that it is entirely practical in how it approaches its subject matter, listing what items should be included and how they should be organised, underlining an approach that fully emphasises the usefulness of a collection to producing knowledge through its display, arrangement and contents. He interchangeably uses the words theatrum sapientiae (theatre of wisdom), conclavium (secure space under lock and key), Kunstkammer (art room), Wunderkammer and museum, and writes upon his title page that it is:

“recommended that these things be brought together here in the theatre so that by their frequent viewing and handling one might quickly, easily, and confidently be able to acquire a unique knowledge and admirable understanding of things.”

What were typically in these cabinets?

If you read anything about these collections, they will typically tell you about four categories of items that most collectors believed should be present:

- Naturalia: Specimens from the natural world

- Artificialia: Objects created, or modified, by humans (this could include manipulation of items from the natural world, such as shells and minerals and corals shaped into artistic objects, as well as arts, antiquities and other historical objects)

- Exotica: Exotic plants and animals

- Scientifica: Scientific instruments

The evolution of cabinets during the seventeenth century, as the Enlightenment approached, was particularly interesting. Collecting curiosities into a cabinet to understand the world around the collector was an abounding cornerstone of creating a collection, and always had been.

As the eighteenth century saw the arrival of the intellectual movement of the Enlightenment, which literally meant the casting of light on new knowledge, collecting became even more popular for people to try and understand the world around them. They also became a great way of displaying your knowledge about science, taste in the arts and objects, and engaging with others who might have similar interests. (I think this why the presence in Bridgerton is PERFECT for Colin and Penelope!)

This was the time of the founding of many societies and organisations that built themselves upon the principles of searching for knowledge: for instance, the Royal Society (founded in 1660) and the Society of Antiquaries (founded 1701 and given a royal charter fifty years later).

It was also a period in which the museum as a public and cultural institution was born. Colonialism and exploration were also a significant part of this, with science and knowledge often given as reasons for trying to colonise other parts of the globe.

Both men and women could create these spaces: piecing together what they knew and had experienced of the world, and trying to understand the parts they did not.

You can hear about cabinets of curiosity and Bridgerton in my Instagram reel below:

Leave a comment