Today is Jane Austen’s 249th birthday, which means we are now officially in her 250th year: I am so excited for all the events and publications (I already have my tickets to tour 8 College St in Winchester), as well as having a few of my own up my sleeve, and so I wanted to start this very auspicious year with a history of something so crucial to Jane Austen and why we still celebrate her today… her publishing journey.

Jane Austen grew up in a household where writing and creative pursuits were not only the norm, but encouraged. You can see that in her juvenilia and early writing, and by 1795, she was writing Elinor and Marianne – an early version of Sense and Sensibility written in the form of letters and correspondence. In October 1796, when she was only twenty years old, she began the novel First Impressions, which would eventually become Pride and Prejudice. It took her just under a year, finishing it the following August. She was twenty-one.

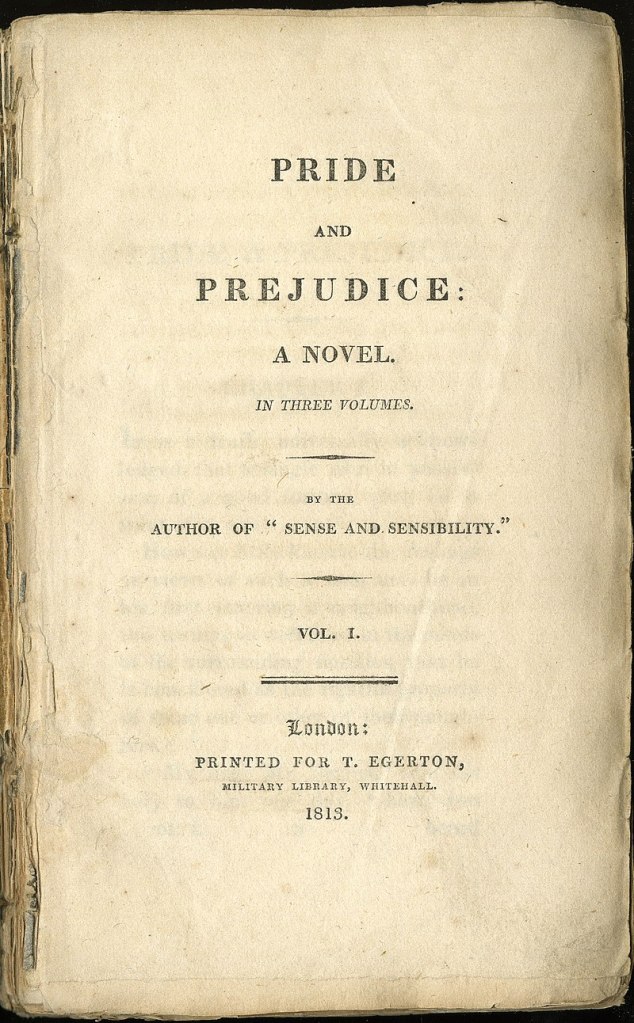

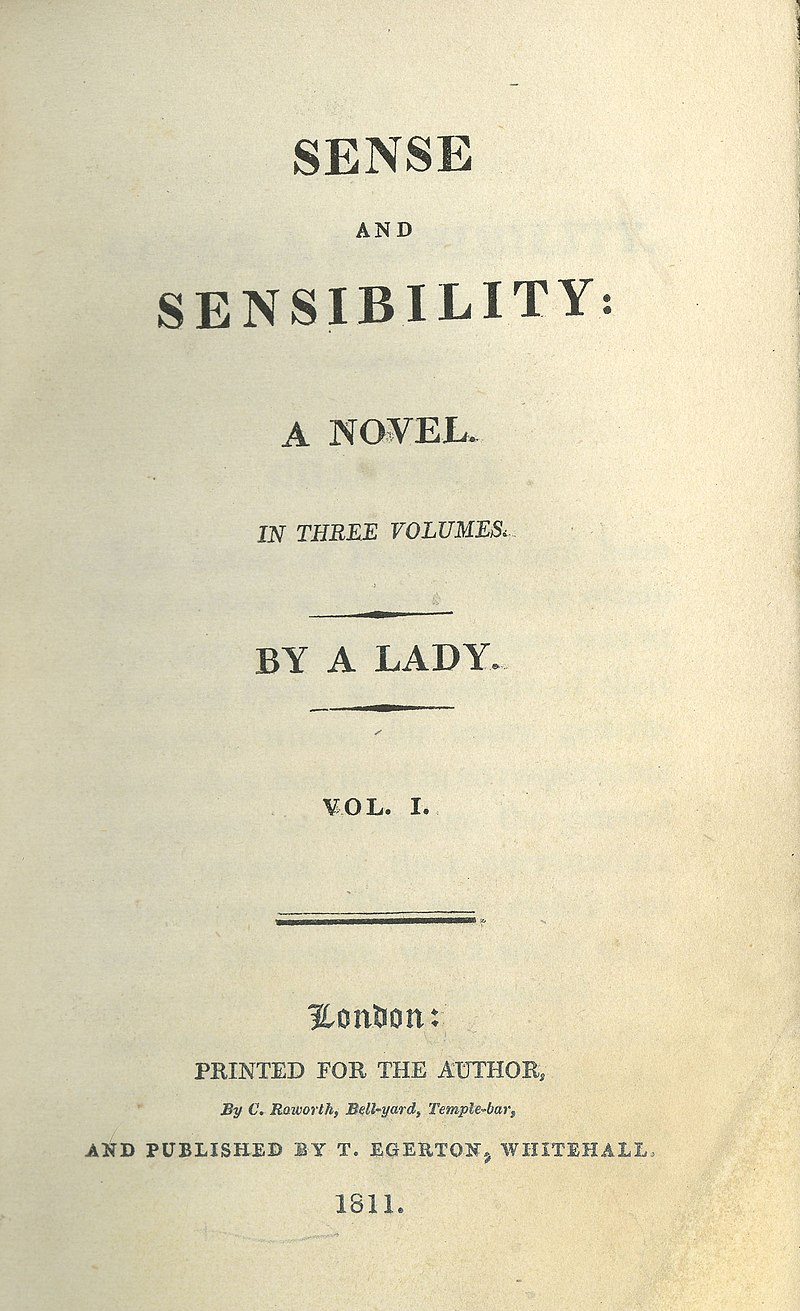

Austen’s ideas and pen were working hard, and she’d produced what would be her first two novels… but they weren’t published until 1811 (Sense and Sensibility) and 1813 (Pride and Prejudice). What happened in between?

Well, her family clearly thought her talent should be shared. A few months after Austen finished First Impressions her father George Austen wrote to London publishers Cadell offering the manuscript, who unfortunately rejected it by return of post.

It must have been a huge blow, but Austen wasn’t deterred. In 1798, she began composing Susan, an early Northanger Abbey. Things changed significantly in Austen’s personal life after this: her father decided to retire from his position as rector of Steventon and move the family to Bath. Steventon had been the centre of Austen’s home life her whole existence thus far, a country village in Hampshire, so living full-time in the hustle and bustle of Bath must have been very different. It was when she was based in Bath that she attempted publication again.

In 1803, with the help of her brother Henry (frequently referred to as her favourite brother) and his lawyer William Seymour, Susan was sold to a London publisher called Benjamin Crosby & Co. The publishers advertised it as forthcoming… but they never published it. I often think it must have been so hard to feel like her dream was within reach, but never quite realised. As the manuscript never saw the light of day, Austen herself tried to buy it back between 1809 and 1811, but could not afford the £10 original purchase price. (And this is definitely a story for another blog post!)

However… at the same time she was trying to get Susan back, Austen finally was getting her publication success. Sense and Sensibility had been accepted by Whitehall publisher Thomas Egerton, who took it on commission. This meant Austen really bore the financial risk, only making money when the original costs were covered. But it meant that in Autumn 1811, readers finally met Elinor and Marianne Dashwood when Sense and Sensibility was published.

Austen was thirty-five years old and her work was finally – officially – out in the world. And it was a reasonable success: by the summer of 1813, the first edition had sold out and she had earned £140. It doesn’t sound very much, and in the grand scheme it wasn’t, but this would have been a significant amount of money for Austen at the time: especially because it was money she had made herself.

Thomas Egerton would buy the copyright of Pride and Prejudice in the summer of 1813 for £110. It went out into the world on the 28th January 1813. It sold out quickly, meaning Thomas Egerton made a lot of profit off Jane’s work. Yet, they did publish Mansfield Park on commission in the spring of 1814… and Jane made £350.

The author of these three novels was beginning to get some acclaim by this point. Of course, we all know they were initially published anonymously: originally ‘By A Lady’, and then ‘By the Author of Sense and Sensibility’, and so on. Even the Prince Regent was a fan, so Austen’s work had managed to get into some pretty illustrious circles. Her brother Henry would tell anyone who’d listen that it was his clever sister who had written such brilliant work, and it was him who offered her next manuscript – Emma – to John Murray instead of Thomas Egerton in 1815.

John Murray, whose house and office is now marked by a blue plaque near the Burlington Arcade in London at 50 Albemarle Street, was the publisher of Lord Byron, and the publishing house would go on to also be the publisher of Charles Darwin and Arthur Conan Doyle. Murray took Emma (with its dedication to the Prince Regent) and published it on 23rd December 1815.

With this success, Austen could finally buy back Susan, and Henry secured it for her in the spring of 1816. Though struggling with illness, she began to revise it. It was reshaped into Northanger Abbey, which, following her death at the age of only forty-one in July 1817, Henry sold it, along with the manuscript of Persuasion, to John Murray. Henry would also write the biographical notice of the author, revealing her identity.

It was not the easiest journey, and Austen suffered many setbacks in her publishing journey. But those six novels have now resonated for over two hundred years across the world: it is astonishing to think, as we enter Austen’s 250th year, that even Jane Austen had work rejected by publishers. Slightly comforting for any aspiring authors out there, I think!

No indeed, I am never too busy to think of S&S. I can no more forget it, than a mother can forget her suckling child; & I am much obliged to you for your enquiries.

Letter from Jane Austen to Cassandra Austen, Thursday 25th April 1811.

Leave a comment